“Most important is our intention to honor the family.”

– Meaghann Shaw Weaver, M.D., Division Chief of Pediatric Palliative Care

My parents were missionaries who did humanitarian, post-civil war community development in Africa …”

In literary circles, it is called a backstory—those defining moments in a character’s past that propel them to who and where they are today. Meaghann Shaw Weaver, M.D., division chief of Pediatric Palliative Care at Children’s Nebraska, has experienced her share of pivotal milestones over the last few decades. The result is a multi-layered backstory that would be right at home in a novella.

“I initially wanted to be a linguistic anthropologist,” she recalls. “I was really interested in studying language, how language evolved and how we’re connected through language. In this post-civil war setting in Africa, if people understood that they actually came from a shared heritage, could they talk more peacefully with each other?”

Dr. Weaver advanced her anthropologic goals by majoring in African Studies and Theology at Creighton University. Then, while visiting her parents back in Ghana, another transformative piece of her backstory emerged: she encountered a patient with osteosarcoma—a child who had to have his leg amputated—and witnessed, firsthand, the vital importance of proper pain management.

“I spent a lot of time at the hospital during his healing time. I ended up developing a close friendship with his oncologist and decided to go into medicine,” she says.

After graduating from the University of Nebraska Medical Center College of Medicine in 2009, Dr. Weaver completed a pediatrics residency at Children’s Hospital of the King’s Daughters in Norfolk, Va.; a fellowship in Pediatric Hematology at Children’s National Medical Center in Washington, D.C., and then a fellowship in Pediatric Oncology/bone marrow transplant at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tenn.

“I found the most exciting and interesting part of oncology was the decision-making for families and the privilege of including adolescents and even young children in decision-making and advance care planning, talking about what their goals are,” Dr. Weaver says.

She came to realize the pathology of oncology wasn’t what intrigued her; it was the “human part” that was really rewarding. Managing pain. Bringing comfort. Listening and being present.

“I discovered there is a field that is entirely committed to relieving human suffering. I was like, ‘That is what I am created to do.’ For me, it was like coming home.”

That field was pediatric palliative care, a holistic and specialized way of caring for children with life-limiting or life-threatening illnesses and their families. Dr. Weaver then pursued a fellowship in pain, palliative care and hospice at the National Institutes of Health. During her fellowship, she volunteered on weekends at a substance abuse disorder clinic and at an urban hospice house for unhoused patients with HIV/AIDS or cancer diagnoses. These experiences revealed to her the impact not only of pharmaceutical interventions, but also the power of dignity for vulnerable community members.

“You have to manage the patient’s symptoms, but you also have to realize there is spiritual suffering in the room; there is existential suffering; there is social suffering; there is relational suffering,” Dr. Weaver said. “We bring to the table things that are often unspoken, and we gently try to lift that or work with families to find their strengths.”

This is where Dr. Weaver’s backstory ends—and the present and future take over.

“Children’s is such a special place,” she says.

Dr. Weaver arrived at Children’s almost two years ago. She heads the palliative care program, Hand in Hand, that was launched as a pilot in 2006 and has since evolved into the only organized, multidisciplinary pediatric palliative care program in the state. The goal is to improve the quality of life for both patient and family by providing relief from the symptoms, pain and stress of a serious illness.

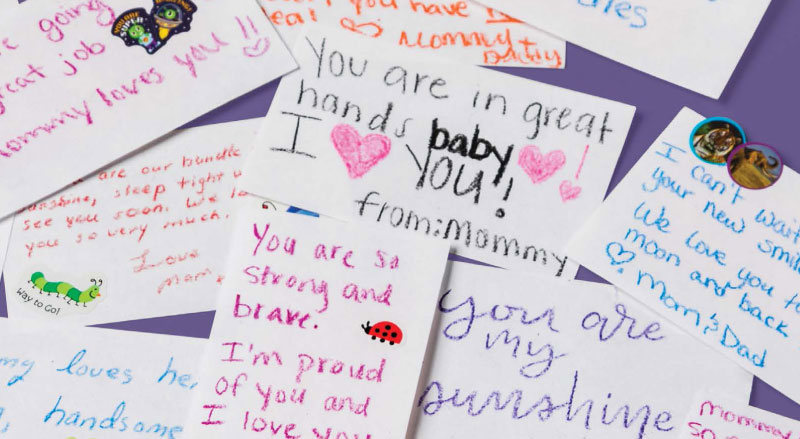

“Most important is our intention to honor the family,” says Dr. Weaver. “The child is the core of our care, but every child is held in a family.”

As such, Dr. Weaver, who incorporates home visits into her practice, is deliberate about also “caring for the caregivers”—parents, grandparents and siblings—making massage, aroma therapy, music, mindfulness, yoga and tai chi available: “It impacts the child if the parent can be calm or can feel like they are getting some form of care.”

A relatively new field, Dr. Weaver said palliative care as an academic division is evolving in very exciting ways. It is becoming more mainstream, for one.

“When I see a cardiologist communicating in a palliative way or when I see palliative partnership with providers, that is the best and most exciting evolution—when it becomes less specialized and more of a primary way we care,” she said. “I also feel quite strongly about advancing the science of palliative care. We’re not just bringing something to the bedside because it ‘seems’ right. We have a heritage of literature for patient-reported outcomes and for metrics. We’re very strategic about researching and educating about impact. The data for impact drives and designs interventions. We’re all about measuring and monitoring implementation outcomes.”

Two years out of fellowship, Dr. Weaver has authored more than 50 peer-reviewed manuscripts; has co-authored the World Health Organization Pediatric Palliative Guide for Healthcare Planners, Implementers and Managers for distribution in low- and middle-income countries; first-authored the American Academic of Hospice and Palliative Medicine Primer Textbook on Pediatric Palliative Care; and has just signed a publication contract for her first children’s storybook (“The Gift of Gerbert’s Feathers”) with royalties donated to a pediatric hospice in Africa.

Outside of work, Dr. Weaver enjoys kayaking, organic gardening, “doing a ton of painting” and, above all, being a mother to her almost 3-year-old daughter, Bravery, a child who possesses the kind of boldness her name reflects.

“She’s incredibly inquisitive and gently spiritual, and she approaches the world with non-judgment. I love watching her walk. She’ll lead with her heart.” Leading with heart is something Dr. Weaver has grown accustomed to at Children’s. She said she has no regrets about not pursuing that career in linguistic anthropology, except one: “I wish I would have learned Kiswahili a little better.”

Her deep connection to African culture—that integral part of her backstory—has helped lead her to the forefront of caring for seriously ill children: “There is a lot of co-parenting in African culture; there is an acceptance of life cycles. That was very formative. Also, there is an acceptance of what Can’t be fixed. There’s acknowledgment of promise even in the midst of peril. There is a reality that there is going to be suffering, but the best thing you can do is stand with someone in their suffering and not shy away from it.”

Doing so means inevitable sadness, but Dr. Weaver said her job also entails an incredible amount of joy: “My metric is not, ‘Is this patient cured?’ My metric is, ‘Is this patient comfortable? Are symptoms managed? Does this patient know they are loved? Is the family together in this? Does the parent know they are parenting well, according to their definition? Does the staff feel purposeful and supported? And even if the outcome is not a cure, could the family reach healing?’ I get to look at healing, which is profound and joyful. I leave very joyful.”